They Felt Your Pain, So They’re Fixing It

A new cohort of athlete-entrepreneurs are designing high-performance gear and equipment designed for the unique bodies (and souls) of women athletes.

[Photo clockwise from top left: Kim Ranalla, Miss Mayfly; Lisa Anthoney, Freyja Fit; Natalie White, Moolah Kicks; Lauren Polstein, Rip-It; Leigh Burns, Lacuna Sports; Mari, Maaree; Kari Traa, KariTraa; Laura Youngson, IDA Sports]

If you're a female athlete, you've felt it: the distraction, pain, discomfort—sometimes even real danger—of athletic gear and equipment that is not designed for the female form.

It’s the relentless pinch of a toebox that’s too tight. The awkward tug of a shirt that doesn’t accommodate your boobs. Nagging worries about too-short shorts, or bleeding through a white uniform. Female athletes are handicapped by a world that treats them as just like male athletes, except, you know, smaller. For girls, just “shrink it and pink it” says a retail cliché, and ignore the rest.

“My experience with my shoes, and my jersey, and the different stuff we wear, even off court, the travel gear, all of it, it is not really cut for us,” says Jori Davis, a star guard at Indiana University, WNBA draftee and multi-year veteran of the European pro circuit.

At its worst, bad design leads to serious injury. Everyone’s talking about ACL tears, and it is well known that girls are at substantially higher risk than boys. Could it be the shoes?

But even less dire issues of comfort (physical or psychological) impact an athlete’s ability to give 100% in competition.“When it comes to how you feel when you get on the court, not having equipment tailored for women means you’ve got all these back-end [worries] going through your mind,” explains Davis. That includes appearance. Professional and college competitors, she adds, “want to look good.”

Lucky for them, in the last few years the sports world has seen a fresh surge of design targeted to women athletes. Startups such as Moolah Kicks, IDA Sport, Rip-It, GoalFive, Paradis Sport, and many more are engaging deeply with female athletes, from Little Leagues to the pros, to understand how to serve them, and delivering innovations that enhance comfort and performance for competition play.

These entrepreneurs are walking in the footsteps of pioneers such as TitleNine Sports, founded in 1989 and a grandmamma in women’s athletic wear. TitleNine’s outdoorwear designs for women opened up the athleisure market, and a key breakthrough product was sports bras. Bras aside, to date that market has generally been mostly about athletic women in solo activities—think hikers, bikers and yogis.

Exploding interest in competitive women’s sports in the last decade has opened new opportunities in the high-performance gear space. Today, IDA is making soccer cleats designed just for women. Rip-It is making softball and volleyball gear just for women, Moolah Kicks is making basketball sneakers just for women. Norway’s KariTraa is making ski gear just for women.

If there’s one thing they have in common, it’s a commitment to learning from their customers. Laura Youngson, founder of IDA Sport, is only half joking when she comments: “I like to say that we do something crazy: We ask women what they want, and we listen to them.”

Well, finally.

We do something crazy: We ask women what they want, and we listen to them.

FIT FOR FEMALE BODIES

In terms of priorities, it’s hard to beat the feet. For most athletes they are the base of all action. Women’s feet are different from men’s—from arches to toe pads to heels. At puberty, girls hips take on a new shape and position, too. “Our feet need to be set for all the other different things that come with a woman’s body,” Davis says.

Yet until very recently, female athletes have had to make do with “unisex” shoes designed for male feet. In 2017, Youngson gathered a global band of women soccer stars to play a record-setting high-altitude soccer match, on Mt. Kilimanjaro, to highlight inequities in the sport. On that trip, she learned that all the professional players were wearing men’s and kid’s cleats, just like she did. What’s more, she learned, their feet hurt, just like hers did. But they put up with it. There was no other option.

That experience was her inspiration to start IDA, and a year later Youngson was at the Dead Sea with a lot of the same competitors, playing a record-setting low-altitude soccer match and testing prototype shoes. In 2020, the company released its first boot.

In addition to testing and feedback with players, IDA works with medical professionals, such as podiatrists, to translate athlete complaints into actionable improvements—“millimeter tweaks in a shoe that then benefit the player.” Recently, feedback on a rugby shoe prototype, for example, led to shifting one of the studs.

But it doesn’t always take a medical expert. When Florida-based Rip-It Sports started interviewing athletes to make better shoes, the answers were almost too obvious. “It didn’t matter what age, every woman, nearly, said ‘I have wide feet’ or ‘I have weird feet,’” says Katie Thompson, Head of Sales at Rip-It for more than four years. “It’s not wide or weird if everyone is saying it.” Thompson, who today owns Mousetrap Fitness in Orlando, FL., says that in the weightlifting/cross-training world there’s a huge emphasis on having a shoe with a wide toe box. “Where that conversation isn’t happening,” she notes, “is in the basketball rooms, the soccer rooms, the softball rooms.”

More recently, in researching volleyball, Rip-It heard that all the jumping and landing meant players were losing their toenails due to feet jamming into the toebox—not to mention the stress on their joints. This led Rip-It to develop a shoe that helps them keep the toenails and (more importantly) reduces the G-forces on the players, according to Vert, an independent testing agency. Similarly, in hoops, New York City-based Moolah Kicks, founded in 2020, is making basketball shoes tailored for women, with female-forward improvements including a narrowed heel and lifted arch.

LISTENING TOURS

Rip-It’s origins were in softball, not volleyball, and they didn’t start with the feet, but at the even more precious head. As a high school competitor, Lauren Polstein got hit in the face wearing a facemask designed for (much smaller) baseballs. So her father (an engineer) designed a new facemask, lighter, and with better visibility. It was a commercial hit. The company expanded into helmets, then into outfitting the softball player from head to toe, and since then into volleyball. Their initial experience grounded them in customer-first design.

“Part of our secret sauce was approaching with no biases. I don't care what I'm going to make for you; you just tell me what I need to do make to make it better,” explains co-founder and former CEO Jason Polstein, Lauren’s brother (yes, it’s family affair). “We created our co-creation process to make sure that it wasn't just some dude sitting around a conference table figuring out what women need for sports.”

That process engages female athletes, from young girls to coaches and pros, in intensive and regular feedback. Sometimes, it means hosting a pizza party, or bringing smoothies to the field, or bringing families for a tour. During Covid, virtual conferencing became easy and accepted, expanding the ability to reach athletes.

And, if they’re young, their parents. “There’s things mom and dad share that the girls don’t always speak to,” says Thompson. “Anything to do with periods. The girls will not tell you that’s a problem, but mom will tell you it’s a problem.”

These companies say there has also been a process of deep engagement and education all along the supply chain. Several in the shoe business told stories of factory managers offering up the standard “last” (a mold of a foot that serves as the framework on which shoes are built), despite having been told the plan was to make a woman’s shoe. Of course the standard last is called “unisex,” but as Polstein notes, “we all know 'unisex' really just means made for boys or men and then sized for girls.”

At GoalFive, the targeted soccer player design of its pocketless Excel signature short and other products won it an intense buyer loyalty. “The inseam, the cut of the shape of the shorts, they’re designed for athletes with traditionally larger thigh and gluteus muscles,” explains Suzanne Currier, chief marketing officer (and an investor) with GoalFive. “And they made sure the fabric stretches and moves as you would need as soccer player.” The nascent enterprise struggled when Covid hit, and the website went semi-dormant for a time. But customers kept checking in, and as soon as the site returned so did the sales.

“It’s amazing how loyal the audience has been,” Currier says. Word of mouth plays a strong role in marketing for all these companies.

LOOKING GOOD, LADIES!

Sometimes, it seems surprisingly easy to make a difference. Softball pants were a major pain point, Rip-It’s research found. Players run the gamut of body types, but there’s always been just one cut: a baseball pant. Rip-It “innovated” softball pants in three different cuts for different body types, but Polstein is modest. “This isn't rocket science,” he points out. “If you’re a woman and you go shopping for jeans, there's more than one option.” Still, in the softball world this change was so profound that at one event, Polstein says, “a dad pulled us aside and told us we were ‘doing God's work’.”

Even in the 21st century, females are judged heavily based on how they look. For athletes, this is in some way a curse, as you want to be judged for your skills. At the same time, you want to look good. You want pants that fit. Volleyball shoes that aren’t “boring.” All your toenails.

Women athletes at all levels make choices for aesthetic, social and emotional benefits as well as performance. Thompson describes a progression of emphasis from looks to performance as athletes age: the youngest girls want pink glitter; tweens get more serious, as they emulate older role models; and high school competitors begin to focus on performance needs. At the top, “Pro and college level athletes, there’s a lot more that they need,” Thompson says. “But aesthetics is still very high on the list.”

Or as Davis puts it: “When you play, [looking good] is part of the whole thing.”

WOMEN’S SPORTS GEAR: WHO BUYS?

These upstart brands, for the most part tightly focused in niche markets, get great validation from end-users—their loyal fans. “We’ve got a thriving direct-to-consumer business, especially through that player-led, player-by-player word of mouth,” says IDA’s Youngson.

They have also done well getting accepted by retailers who sell directly to end users. “The big box retailers were phenomenal and very progressive,” says Thompson, whose sales job at Rip-It put her on the front lines with business customers large and small. Dick’s Sporting Goods, which had Lauren Hobart as CEO starting in 2021, was very open to featuring more products for girl athletes; several of the companies featured in this story won space on its shelves.

But in team sports, individual players don’t get to choose. Purchasing decisions are made by coaches, or the team, or league, or school, sometimes on giant contracts that don’t prioritize girls. At the collegiate level, Thompson explains,“you have the challenge of ‘this university is sponsored by ABC brand, so we can’t talk to you.’” Furthermore, she adds, “the decisions are typically based on the men’s football team or the baseball team or however the sponsorship agreement will bring in the most money.”

“It’s insanely hard to break through against the big dogs of the world, the Adidas’ and the Nikes,” says Currier, noting that GoalFive is aiming at a different customer.

GIRL STUFF

Even in league or smaller school settings where coaches do have some decision-making power, male coaches (and most coaches are still male) aren’t always open to “girl issues.” Talking about period protection products, or volleyball shorts that are 5 inches long instead of a skimpy 3 inches, make male coaches just as uncomfortable as the teenage girls on their teams.

“The ones that were the most open to the conversation were the ones with large families and lots of daughters,” Thompson noticed.

It doesn’t serve girl athletes to be squeamish about their bodies. Girls’ participation in sports declines noticeably with increasing breast size—just one way puberty hits girls. A 2024 article in Psychiatric Annals, Unique Considerations for Female Athletes: A Psychiatric Perspective, lays out some of the ways that the changes of adolescence impact girls’ capacity in sports more than boys’.

The authors—doctors and psychiatric specialists Cindy Miller Aron from the University of Wisconsin; Carla D. Edwards of McMaster University in Toronto; and Pamela Weatherbee from the University of Calgary—point to several impacts of hormonal and endocrinological differences between the genders. For girls, body morphology, muscle development and fat distribution change markedly in puberty—and more dramatically than for boys. Menstruation, in addition to potentially embarrassing leaks, actually impacts ligament laxity (and thereby joint stability), and is thus a suspected factor in girls’ high risk of injury and longer recovery times. Same for concussions. “Research suggests that menstrual cycle phase at the time of concussion is predictive of outcomes among women,” the authors note. Social pressure is harder on girls too, with anxiety and eating disorders more common among female athletes.

WOMEN ATHLETES: FINDING UNITY

The idea of designing for women has taken hold across an impressive array of sports. Freyja Fit makes weights and equipment for women weightlifters. Lacuna Sports, born in 2019, offers a full cricket kit designed for female players, and is soon to release one designed with hijab—significant, given the sport’s popularity in Muslim countries. At MissMayFly.com, lady flyfishers can now get waders just for them—with options for bodies that are slim, curvy, full and more. “Finally!” enthused Sania, a happy customer, in a website review: “I am able to move with ease, stay dry and still look cute.” Other waders, she added, “felt like I was wearing a garbage bag with suspenders.”

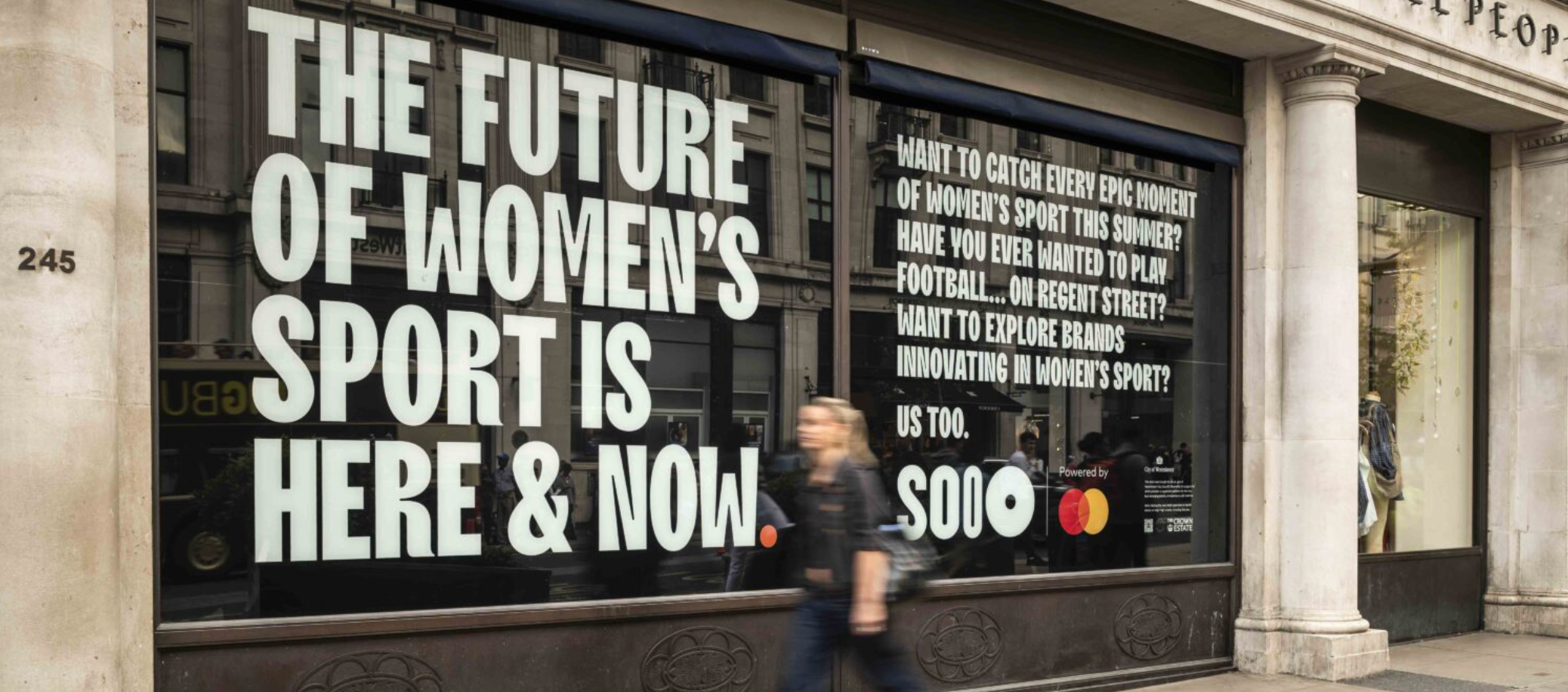

In London this summer, a pop-up store in Regent St. organized by IDA showcased women-oriented sports-related businesses, including Paradis Sport (underwear), Foudys (soccer kits), Boob Protect (guards), and some two dozen more. More an experiential space than mere shop, it included watch parties, fitness classes, kids events and a soccer pitch.

In other words, it was a space that aimed to do more than sell clothes or shoes, but to nurture girl athletes and promote opportunities for women’s sport. These entrepreneurs are driven by a larger sense of mission. Most are partnered with one or more nonprofits or like-minded businesses that also seek to empower and encourage female athletes.

“Everyone is willing to help each other. It’s heartwarming and kind of re-sets my perspective at work and in life.” Currier says. “There are several like-minded companies who have the same common goals, and although we are natural competitors in life, as women in these roles helping lead these brands, we are a community and want to uplift each other and see that as a path to success all around.”

What’s next for these companies and the athletes they serve? They’re all driven to keep innovating. Rip-It just released a new softball shoe, the Ringor Pro. Its segmented sole offers the athlete better movement, prompting Polstein to brag that this may be “the first time in the history of the world that the girls have a better product than the boys.”

Youngson is currently testing a “secret” soccer cleat to be released next year, and for IDA, expanding into new sports is happening naturally. “We pick up players anyway,” Youngson says. “We’ve been working with the US lacrosse team. We know rugby, flag football players wear our shoes.”

But she feels no call for IDA to compete with those making underwear or jerseys for women athletes: “We know we make shoes exceptionally well, so we’re just going to keep making brilliant shoes.”

There’s no denying the growth in women’s sports, some of it very recent. In 1971, girls accounted for just 7% of all high school varsity athletes; by 2001, they were 41.5% of all varsity athletes, according to the National Coalition for Women and Girls in Education.[21]

And there has been much more recent growth, from girls' participation in schools and leagues to the formation of professional leagues. The WNBA played its first game in 1997, and just earlier this year, two WNBA superstars launched an off-season 3 on 3 league, Unrivaled. The National Women’s Soccer League began play in 2013, after a few false starts. Women’s ice hockey also saw a few false starts, with today’s Professional Women’s Hockey League starting play as late as 2024, having swallowed what began in 2015 as the National Women’s Hockey League. Pro lacrosse began only in 2021. The Pro Volleyball Federation began play as recently as 2024.

New leagues are forming—and old leagues finding firmer ground—due to growing market demand. Women’s sports are popular. “It’s beautiful that the women’s game is growing and now everyone sees the opportunity,” says Jori Davis.

That is opening up new markets for sports gear and equipment tailored for these high-performance athletes.

“Society has responded to the demonstration of female athletic prowess with record-breaking viewing and attendance records for events, and professional sports leagues for women have emerged and expanded over the past 5 years,” Doctors Aron, Edwards and Weatherbee comment in their paper. “The world is watching, and the sports world is learning.”

When it comes to serving women athletes, much remains to be learned, but these entrepreneurs are already delivering for them on fields, courts, and pitches around the world.

Check out our expanding guide to companies changing the game through women-first design.